We recently conducted a mock trial on a significant case. The jurors were very typical for what we expect to see in a Manhattan jury. After each argument or witness, each juror answered a handful of excellent feedback questions—and all their answers flowed across our monitors, in real time.

It was fascinating to see how far the technology has advanced for generating objective feedback from lay people. We were awash in great insights!

However, as the attorneys made their arguments one of them happened to use the term “red herring.” Nobody thought this was a controversial term. In trying many jury trials, our clients have, conservatively, dished out “red herring” hundreds of times in front of jurors. It never dawned on us that the term might confuse or befuddle jurors.

But upon hearing “red herring,” our First Court consultant did something very interesting. He asked the jurors this question: “In your own words, what is meant by the term 'red herring’?”

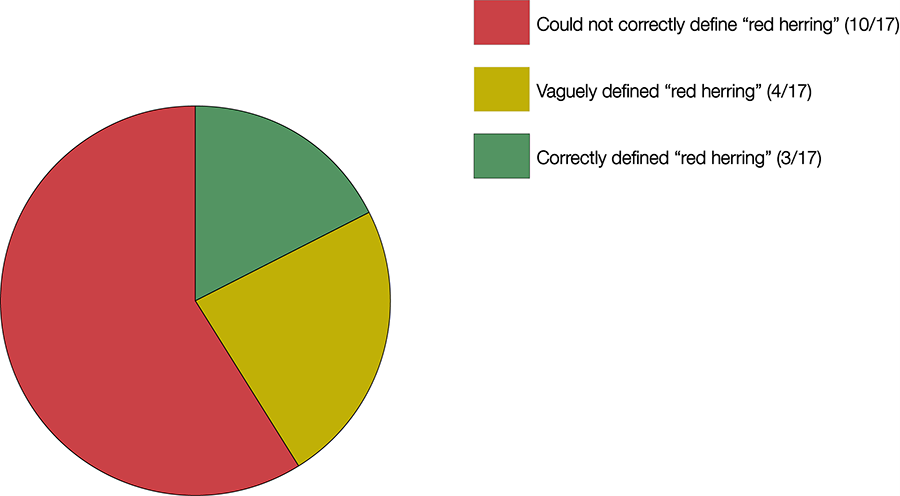

The results shocked both of us:

To be blunt, the responses provided by the jurors overwhelmingly supported the belief that jurors would not understand the term. Out of the 17 total respondents—who represented a wide range of educational backgrounds and demographics—only three could define the term reasonably accurately, while four more had a vague, approximate sense of the term's definition. Ten people simply did not understand the term—eight of those ten were willing to admit it, while the other two tried a definition, and got it completely wrong.

Our research into this particular instance of legal jargon was helpful not just because it suggested that we should be wary of using even apparently basic, commonly used terms that have wider purchase than law. The research also broadened our reasoning for avoiding such terms.

There are three dangers with using terminology that jurors don't understand:

- You create a HUGE psychological distance between you and them. They learn, quickly, that they can’t understand you and that they don’t belong. That is a communications and advocacy disaster! Even if the facts and the arguments are on your side, you’re making your job potentially insurmountably more difficult when you alienate your jurors.

- They will tune out, become more easily distracted, or simply stop caring. For the jurors, ignorance will be bliss compared to listening to you—and their resulting indifference will be a nightmare for you.

- They’ll more susceptible to non-rational factors such as emotion and body language when evaluating testimonies and evidence. Jurors are already hugely swayed by these non-rational factors. When you’re making your arguments, you need to give yourself every chance of getting through to them. Using vocabulary that makes you seem like you’re speaking a foreign language won’t help.

The plain language movement in legal writing nearly always emphasizes the plain writing of legal documents. But our research for this case suggests that trial lawyers can also benefit from being more aware of the scope of legal jargon and the potential effects that the use of that jargon has on juries. By defaulting to simpler words rather than fancy, complex ones, trials lawyers will be better able to maintain their juries' attention, focus, and awareness. Revenge is a dish best served cold; in court, red herring is best not served at all.

Tags:

Aug 16, 2022 11:15:06 AM

Comments